In February of 2016, Fantastic Stories of the Imagination published an essay I wrote called “A Crash Course in the History of Black Science Fiction.” Since then, Tor.com has published my in-depth essays on sixteen of the 42 works mentioned. In this seventeenth column I write about Nalo Hopkinson’s second novel, Midnight Robber.

STOLEN SWEETNESS

Using variant speech patterns—the multiple patois of the many different Caribbean islands in her background—Hopkinson creates a honeyed symphony of words redolent of the newly settled world of Toussaint’s imported Island culture. Days after finishing the book, its phrases still ring in my mind: “Born bassourdie…What a way things does grow…Music too sweet!” As the prefacing poem by David Findlay declares, for colonized peoples, telling stories in any form of English is a way of appropriating one of our colonizers’ primary tools of oppression. Telling stories that deprivilege the status quo is a doubly subversive tactic, and that’s how Midnight Robber’s heroine, Tan-Tan, overcomes the awful odds against her.

Using variant speech patterns—the multiple patois of the many different Caribbean islands in her background—Hopkinson creates a honeyed symphony of words redolent of the newly settled world of Toussaint’s imported Island culture. Days after finishing the book, its phrases still ring in my mind: “Born bassourdie…What a way things does grow…Music too sweet!” As the prefacing poem by David Findlay declares, for colonized peoples, telling stories in any form of English is a way of appropriating one of our colonizers’ primary tools of oppression. Telling stories that deprivilege the status quo is a doubly subversive tactic, and that’s how Midnight Robber’s heroine, Tan-Tan, overcomes the awful odds against her.

BABY STEPS

Midnight Robber begins in Cockpit County, a sophisticated human settlement on the aforementioned extrasolar planet of Toussaint. Tan-Tan is seven. Her feuding parents tear her heart apart between them, and eventually she and her father Antonio must leave for Toussaint’s transdimensional prison world, New Half-way Tree. There Antonio sexually molests Tan-Tan, driving her into the wilderness. With the guidance of indigenous sentients she thrives and lives a life of adventure punctuated by crusading raids to punish evildoers in the prison world’s isolated villages. Masquerading as the Midnight Robber, a poetry-spouting figure familiar to all who attend the Caribbean’s Mardi Gras-like carnivals, Tan-Tan inspires tall tales, by the age of seventeen turning herself into New Half-Way Tree’s homegrown hero.

GIANT LEAPS

Hopkinson accomplishes so many wonders with this novel that it’s worth taking time to enumerate them. First, in case you missed what I said earlier, I’ll mention again the sheer beauty of Hopkinson’s prose. Combining the dancing polyrhythms of a panoply of Caribbean vernaculars with thoughtfully interpolated standard English, her dialogue and her vivid descriptions of character, settings, and action move, groove, charm, and chime together in deepest harmony. The story is sometimes funny, sometimes tense, sometimes tragic, and always utterly involving. My favorite passage in Midnight Robber is when Tan-Tan, tired of the live food and alien housekeeping protocols of a douen village, snarks at her reluctant hosts: “Oonuh keeping well this fine hot day? The maggots growing good in the shit? Eh? It have plenty lizards climbing in your food? Good. I glad.”

Second, Hopkinson depicts the presence of African-descended founders of interstellar colonies as a given. Axiomatic. No need for discussion or speculation as to how that could occur. It simply does.

Third, she shows the denizens of New Half-Way Tree dealing with the native douen in ways that mirror the patronizing attitudes whites have historically held toward blacks, throwing the humans’ ridiculousness into stark relief when they call one “boy,” or refer to the species as a whole as “superstitious.”

Fourth, appropriating a riff from male-centric buddy movies, Hopkinson pits Tan-Tan in a knock-down, drag-out fight against the douen woman who afterward becomes her friend. Like Eddie Murphy and Nick Nolte in 48 Hours they pound each other into the ground—no hair pulling “hen fight” moves—then bond for life. (This is just one example of the author’s gender-unbending strategies.)

Fifth, though Tan-Tan’s home planet Toussaint is a techy wonderland, there’s a revolution in the works. Runners and others who disagree with the colony’s anti-labor attitude (“backbreak not for people”) band together to find relief from their constant nano-electrical surveillance by the “Nansi web.” They learn to disable the web’s agents, communicate by writing on “dead” (non-digital) paper, and live communally in houses immune to web-enabled spies. One person’s Utopia is another’s nightmare.

Sixth, nonstandard sexuality is everywhere. Toussaint’s proletarian runners practice polyamory. A pair of blacksmiths on New Half-Way Tree are kinky for footplay and Dominant/submissive roles. The self-appointed sheriff of one prison-planet settlement has married a partner of the same gender. None of this is a cause for shame. None of it is criminal.

Seventh, the categories of difference described by Hopkinson are far from monolithic. Though it could be (and has been) called “Caribbean-colonized,” Toussaint is genetically and culturally diverse in the same way the Caribbean itself is, with its heritage deriving from indigenes, South Asians, European settlers, and enslaved and imported Africans of several nations. Likewise, on New Half-Way Tree, the social systems found in its settlements range from the corporatized peonage of Begorrat to the neighborly socialism of Sweet Pone.

GREATNESS OF SIGNS

All these wonders are encompassed in the widest wonder of all: the tale Hopkinson tells. Midnight Robber entertains SF readers while also modeling how speculative fiction can rescue them. Tan-Tan heals her wounded life with words, and words are what Hopkinson prescribes for us—especially those who’ve been marginalized—as we seek to save our ailing world from crisis after crisis. When Tan-Tan faces down her enemies, a mythological figure’s nonsense utterances entrance those who would harm her. Mystical roundaboutation makes of each incident an unfolding story rich in meanings its audience feels they must divine; verbal tricks elicit admiration and respect for the performer in Tan-Tan’s case—or, in the case her emulators, for the author.

“Corbeau say so, it must be so,” Tan-Tan sings to herself while preparing for freedom from the living curse known as Dry Bones. I like to paraphrase that song’s lyrics slightly, subbing in Hopkinson’s name: “Nalo say so, it must be so.” I like to remind myself and other authors that we have work to do. To put that reminder in Midnight Robberese: “Come, let us spake the fake that makes whole truth of nothingness, of notness, of mocking talking future walking out of sight and out of minding any unkind rules for fools. And let us be our own best blessing, never lessing, always yessing light.”

Nisi Shawl is a writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories and a journalist. She is the author of Everfair (Tor Books) and co-author (with Cynthia Ward) of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov’s SF Magazine, Strange Horizons, and numerous other magazines and anthologies.

Nisi Shawl is a writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories and a journalist. She is the author of Everfair (Tor Books) and co-author (with Cynthia Ward) of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov’s SF Magazine, Strange Horizons, and numerous other magazines and anthologies.

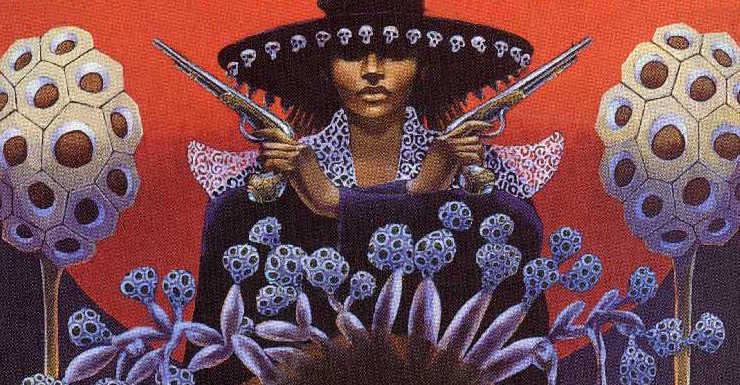

Who did the cover art. They are very L&D Dillon-esque, but they can’t be, can they?

Yes, it’s Leo and Diane Dillon! I was so jealous when I saw it!

Might be worth mentioning it was published in 2000, was nominated for a Hugo and is still in print. To Amazon!

Love this book!

Ha, I picked up The Midnight Robber on Audible the day before this article came out. The audio book is read by the redoubtable Robin Miles who really makes the language of this novel sing.

Hey Nisi,

First off, thanks for this, honestly very cool, recommendation. I plan on grabbing it ASAP. I hate to admit that I just stumbled on this post due to Tor’s newsletter, but I’ll be working my way back through your reviews and trying to read ’em all!

One request, your crash course essay doesn’t appear to be available anywhere. Your link doesn’t work, and I can’t seem to find it online anywhere. Would you be willing to share another link or possibly point me to a place where you have published it? I’d love to have access to your whole list, as I’m doing my master’s in education and am working on a multicultural literature focus. You can imagine how much I’s love to read each and every one of your recommendations!

Thanks!

@6, here you go: https://www.tor.com/tag/history-of-black-science-fiction/

John (#6) I found out this weekend that the site where the original article was published is down–temporarily, per its publisher, but such an inconvenience! Meanwhile, my original list plus three additions can be found here: https://www.goodreads.com/list/show/97673.A_Crash_Course_in_the_History_of_Black_Science_Fiction (#7, that link shows the Expanded versions of 16 works, but not the original list of 42. But thank you!)

Hey Nisi and filkfernengi,

Thabks for pointing me to the list! I’ll definitely work my way through it whenever I have spots in my schedule for fun reading!

Nisi, you wouldn’t happen to have a newsletter or a personal blog, would you? Would love to get notified whenever you post a new entry!

Thank you for this. It’s now on my (unfeasibly large) to read list.